It melts.” “Photosynthesis.” “Yes.”

Early in my science teaching career, I often received short answers like these on tests and quizzes—and I didn’t think twice about it. As long as students got the content right, I felt I couldn’t fault them for not writing in complete sentences. Writing, after all, was the English teacher’s job—wasn’t it?

But over time, I realized that this approach was limiting to my students. Many still gave half-formed responses and incomplete thoughts, which made it harder for them to fully grasp scientific concepts. Writing, I’ve come to see, isn’t just a means of communication—it’s a way of thinking. It helps students organize ideas, make sense of new information, and develop deeper understanding. When we don’t teach them how to write in science class, we also hold back their ability to think in science.

Cognitive science supports this shift in thinking. Scholars like E.D. Hirsch have long emphasized the importance of background knowledge in comprehension (Hirsch, 2016). To help students truly understand science, we must give them opportunities to write about the content—not just label it. Writing helps them process and internalize that knowledge in meaningful ways.

Why Writing Strengthens Science Learning

Research (Barshay, 2020; Hochman & Wexler, 2017) shows that writing about academic content strengthens learning. When students write, they must clarify their thoughts, deepen their understanding, and make connections—much like having a thoughtful conversation. In fact, writing not only clarifies thinking, but also boosts memory and retention.

If a student can’t write a clear sentence about a concept, chances are they haven’t fully understood it. The struggle to express ideas in writing can actually drive deeper thinking. Studies (Barshay, 2020; Hochman & Wexler, 2017) confirm this: writing in subjects like science reliably improves learning outcomes across grade levels. Writing isn’t just a literacy skill—it’s a thinking tool. These findings align with Hirsch’s belief that knowledge-building in early grades is essential. When we embed writing into science instruction, we help students both learn and remember what matters.

The Writing Revolution: Where Literacy Meets Science

One resource that helped me bring writing into my science teaching is The Writing Revolution (TWR), created by Judith Hochman and colleagues. TWR offers clear, practical strategies for integrating writing into all subjects—even science. Rather than treat writing as something that only happens in English Language Arts, TWR embeds it directly into content lessons.

According to its authors, TWR is “as much a method of teaching content as it is a method of teaching writing.” One of its most accessible tools is the use of structured sentence stems—such as because, but, and so. Students begin with a basic factual sentence, then extend it using one of these conjunctions. The result? A richer explanation, deeper thinking, and stronger science learning.

This strategy doesn’t feel like an “extra.” It feels like the kind of critical thinking we want in any science class. It turns content into conversation—and science teachers into literacy teachers in the best sense.

A Grade 5 Example in Action

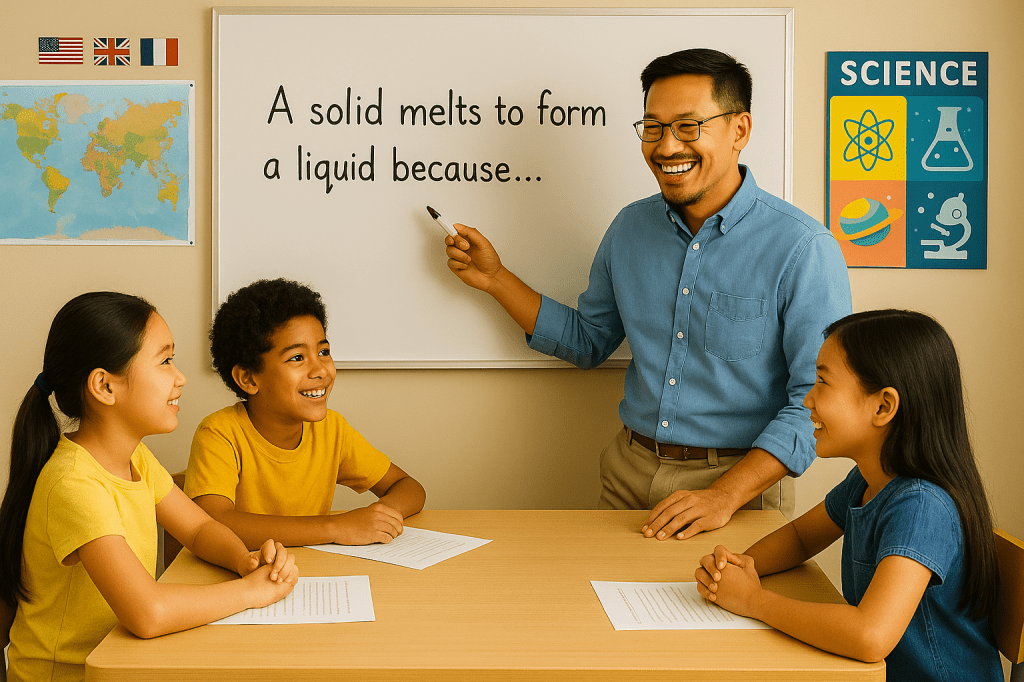

Curious about how this would work in practice, I experimented with what TWR might look like for a grade 5 physical science unit.

A typical question in a grade 5 matter unit might be , “What happens when a solid is heated?” And the familiar answer would be: “It melts.” However, what if the teacher gave the students a sentence stem—“A solid melts to form a liquid…”—and then asked them to complete this sentence using because, but, and so. Here’s what they might respond back:

- A solid melts to form a liquid, but it can also sometimes sublimate into a gas.

- A solid melts to form a liquid because heat makes its particles move faster and spread apart, causing the material to act like a liquid.

- A solid melts to form a liquid so a glacier is really water waiting to happen. (Lemov, 2014)

What once was a one-word response becomes a mini writing task. And these sentences reveal students’ understanding of concepts like sublimation, molecular behavior, and real-world applications far more clearly than our original two word answers. Hence writing in science can also double as an effective tool for review and assessment.

Conclusion: Why Writing Belongs in Every Science Class

Bringing writing into the science classroom will reshape how our students engage with science content. Structured writing helps them move beyond memorization and into critical thinking. It encourages them to connect ideas, articulate their understanding, and make science their own. Writing isn’t a distraction from science—it’s a gateway into it. Let’s make writing a central part of how we teach science.

References

Barshay, J. (2020, November 16). Proof points: Evidence increases for writing during math class. The Hechinger Report. Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://hechingerreport.org/proof-points-evidence-increases-for-writing-during-math-class/

Hirsch, E. D. (2006). The knowledge connection. American Federation of Teachers. https://www.aft.org/ae/spring2006/hirsch

Hirsch, E. D. (2016). Why knowledge matters: Rescuing our children from failed educational theories. Harvard Education Press.

Hochman, J. C., & Wexler, N. (2017). One sentence at a time: Teaching writing across content areas. American Educator, 41(2), 4–11. Retrieved June 3, 2025, from https://www.aft.org/ae/summer2017/hochman_wexler

Hochman, J. C., & Wexler, N. (2017). The writing revolution: A guide to advancing thinking through writing in all subjects and grades. Jossey-Bass.

Lemov, D. (2014, August 19). Hochman’s ‘But, Because, So’ sentence expansion activity. Teach Like a Champion. https://teachlikeachampion.org/blog/hochmans-sentence-expansion-activity/

Willingham, D. T. (2009). Why don’t students like school? A cognitive scientist answers questions about how the mind works and what it means for the classroom. Jossey-Bass.

Leave a comment